We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land on which the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art stands and recognise the creative contribution First Australians make to the art and culture of this country.

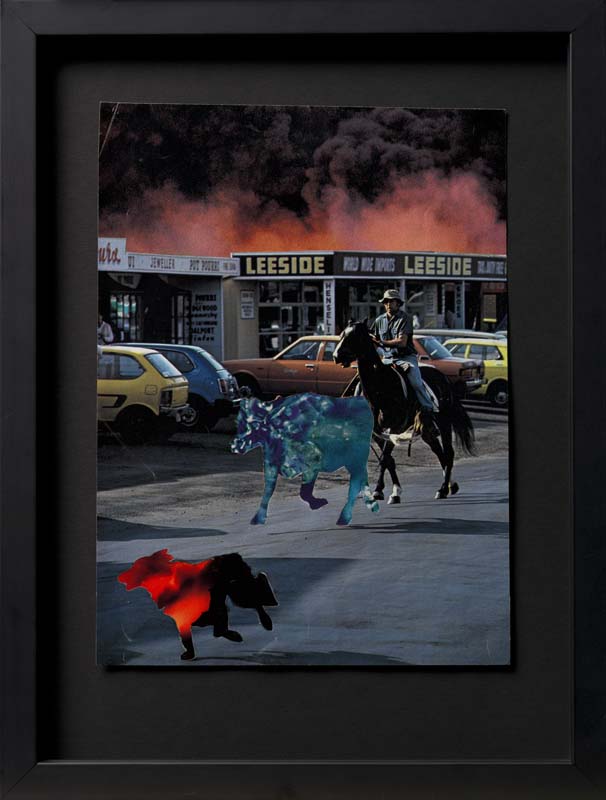

Peter Madden / New Zealand b.1966 / The Nimble Jackal, It’s Face A Grimace Of Grasping Teeth “There are Gates Within Gates Within Gates” A Man Rolls His Right Eye In And Out To & Over A Rarely Preserved Ancient Mushroom And The Mushroom Said “Dead Mans Bread Death Days With Flesh Of The Deities Crystal Skull (Below) Is Attributed To A Knife Tongued Coyote (Right). An Inmate (Above)” 2005 / Watercolour, metallic foil and collage, 8 panels: 32.5 x 24.8 x 2cm (each, framed) / Gift of Henry Ergas through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation 2010 / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Peter Madden

Peter MaddenThe Nimble Jackal, It’s Face A Grimace of Grasping Teeth “There Are Gate Within Gates Within Gates” A Man Rolls His Right Eye In And Out, To & Over A Rarely Preserved Ancient Mushroom And The Mushroom Said “Dead Mans Bread Death Days With With Flesh Of The Deities Crystal Skull (Below) Is Attributed To A Knife Tongued Coyote (Right). An Inmate (Above)” 2005

Not Currently on Display

In today’s world of unrelenting visual stimuli, it is necessary to process imagery — especially the photography in advertising, billboards and magazines — in the blink of an eye, and then move on or risk drowning in it. Peter Madden’s intimate suite of eight photograph-based collages defies such fleeting assessments. The brain’s processing reflex is pulled up short by Madden’s subverting of otherwise recognisable scenes and objects.

Some works, like the image of psychedelic bubbles floating away from an Islamic temple, are poetically realised fantastical worlds. Others are like the pictorial equivalent of a word association game that gets progressively stranger as it goes on — waitresses with seal heads and antlers take a break in a scene recalling something from Douglas Adams’s restaurant at the end of the universe.1

Endnotes:

1. The Restaurant at the End of the Universe (1980) is the second book in Douglas Adams’s quirky The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy series.

Peter Madden willingly submerges himself in imagery overload every day. ‘Obsessed’ is the word he uses when it comes to photography and his practice. His is an old-fashioned obsession — he eschews the internet for the printed page, poring over old copies of National Geographic. The instant wizardry of Photoshop is also not for him — his collages are created with scalpel and artisan hands. His work seems driven by the need to liberate images from their original context, as though each is waiting impatiently within the covers of a magazine or book, predestined for another, much more interesting life in one of the artist’s created worlds.

Madden also makes wonderfully elaborate three-dimensional papercut and sculptural works, and there remains a strong connection between these and his 2-D collages: ‘I suppose the 3D objects always had a surface of collage, of fragments that slipped and fluttered over and within them’. It is these fluttering and slipping fragments that make Peter Madden’s visual worlds — worlds that seem to tap directly into a constantly dreaming subconscious — so elusive and compelling.