We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land on which the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art stands and recognise the creative contribution First Australians make to the art and culture of this country.

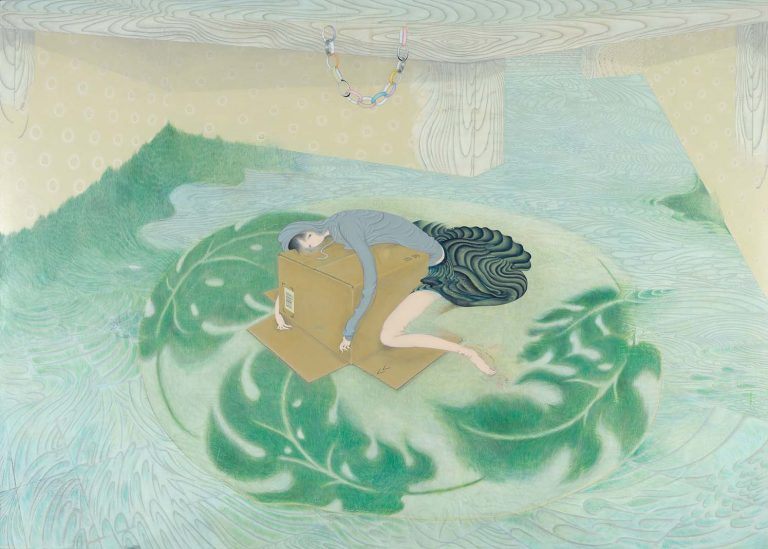

Tomoko Kashiki / Japan b.1982 / I am a rock 2012 / Synthetic polymer paint, masking tape on linen on plywood / 162 x 227.5cm / The Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Collection of Contemporary Asian Art. Purchased 2013 with funds from Michael Sidney Myer through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Tomoko Kashiki

Tomoko KashikiI am a rock 2012

On Display: Regional Touring Exhibition

Tomoko Kashiki’s women all radiate a strange, glamorous presence. Anatomical correctness is forgone in favour of a form that suits the emotion or whim of the artist. Each is articulated with an organic translucency, embodying the patterns of the background landscape and giving them a decorative substance. The artist’s concept of beauty is as fluid as the ethereal figures she portrays.

I am a rock depicts a woman straddling an upturned, open cardboard box. Her fortress has been infiltrated by water, but, as she floats on her leaf raft, her penetrating gaze is more assured than desperate. ‘Hiding in my room, safe within my womb; I touch no one and no one touches me’, sang Simon and Garfunkel, ‘I am a rock, I am an island’.1 The figure may be isolated, but she appears buoyantly independent.

Kashiki’s paintings have an energy born from the artist’s struggle to unify opposing forces — impermanence and permanence, tradition and innovation, presence and absence, superficiality and substance. Kashiki uses paint to express thoughts and feelings that would otherwise be difficult to articulate.

Endnotes:

1. Simon and Garfunkel, ‘I am a rock’, The Paul Simon Songbook, CBS, 1965.

Sketched out in pencil, then painted in acrylic on fine cotton cloth, Tomoko Kashiki’s paintings are mounted on wooden boards with bevelled edges that create a subtle separation from the walls on which they are hung. On first glance, the paintings bear a strong resemblance to nihonga (traditional Japanese painting), in which Kashiki was trained.

Her surfaces, however, are created by layering the non-traditional material of acrylic paint, which is applied to the canvas, sanded back and repainted, with the process repeated again and again. This technique — and Kashiki’s fine and ghostly painterly style — evokes a range of historical and contemporary references: Heian Buddhist painting, the delicate nihonga of Seihou Takeuchi, the iconic bijinga (images of beautiful women) of Shoen Uemura, and the early canvases of Takashi Murakami.

The women in Kashiki’s paintings, typically depicted in domestic environments or engaged in activities like eating or bathing, are almost always artfully distorted. Shifting between the ethereal and the substantive, some sections of their bodies fade into the background while others sit above it; in the depiction of some, the precise nexus of layers is ambiguous. Their elongated limbs curve in graceful yet uncanny arcs, conforming less to the logic of anatomy than the stylistic requirements of the artist’s works.