We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land on which the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art stands and recognise the creative contribution First Australians make to the art and culture of this country.

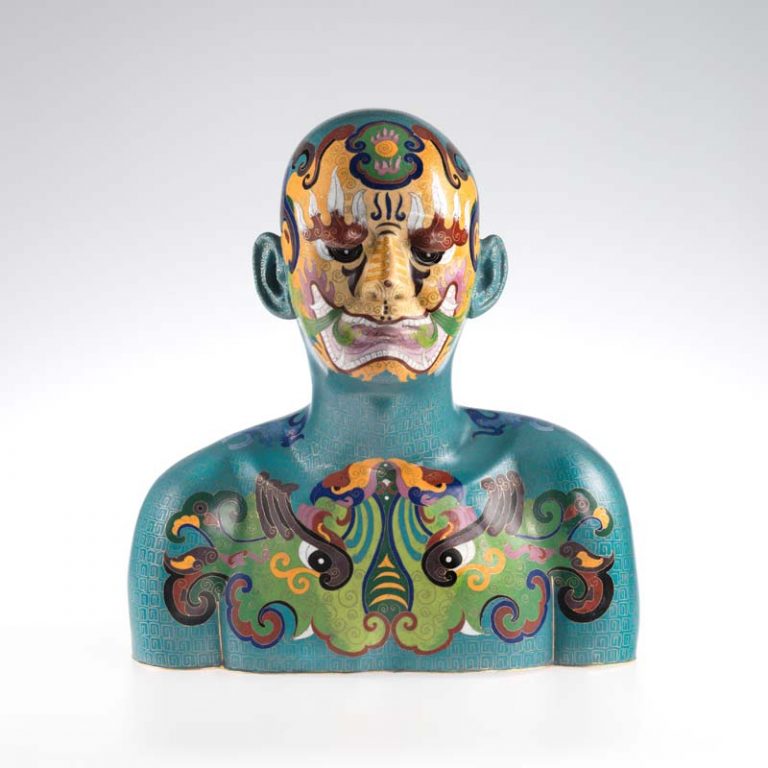

Ah Xian / China/Australia b.1960 / Human human – Bust no.5 2002 / Hand-beaten copper, finely enamelled in the cloisonné technique / 43cm (ht.) / Purchased 2009 with funds from Tim Fairfax AM through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Ah Xian

Ah XianHuman human – Bust no.5 2002

Not Currently on Display

This sculpture is part of a major series of works entitled ‘Human human’, in which Ah Xian which moved away from porcelain into other techniques. Human human – Bust no.5 is made using the traditional cloisonné technique, with the assistance of craftsmen from Jingdezhen. Filigree copper wire defines the designs that have been filled with enamels, which are then fixed and the figure is immersed in an acid bath. Once this is done the sculpture is fired in a large earth kiln at low heat.

In this work, as with many of his busts, Ah Xian uses an all-over design that creates strange and surprising conjunctions between the image and the features of the face. Using traditional decorative design elements such as flames and dragons, Human human – Bust no.5 features a symmetrical design over a blue-green ground, a colour that in traditional Chinese physics, symbolises one of the five elements, wood, which references spring and thus vitality and life.1 The figure appears to be wearing a demonic mask, at odds with the calm features of the sculpted face. On the crown, chest and back of the figure, Tao Tieh dragon motifs appears like tattoos, which have been suggested in discussions of Ah Xian’s work as making a statement about the indelibility of one’s cultural background.2

Ah Xian’s sculpture deals with the paradoxical – with tranquility and disruption, beauty and aversion, tradition and innovation, life and death. The final impression is of a delicate balance between all these possibilities. Poised between cultures and countries, between old and new, the art of Ah Xian is an attempt to reconcile his past and present lives.

Endnotes:

1. Catalogue note, ‘Ah Xian’, ‘Important Australian Art, Melbourne 24 & 25 August 2009’, auction catalogue, Sothebys, Melbourne, p.136.

2. ‘China Refigured: The Art of Ah Xian’, Asia Society and Museum, New York, 2003, <http://www.asiasociety.org/arts-culture/asia-society-museum/past-exhibitions/china-reconfigured-art-ah-xian>, accessed 7 September 2009.

A self-taught painter, Ah Xian began working as a professional artist in China during the 1980s. In early 1989 he visited Australia for the first time for an artistic residency at the University of Tasmania’s School of Art, returning to China only weeks before the confrontations at Tiananmen Square on 4 June 1989.1 The following year, Ah Xian and his artist–brother, Liu Xiao Xian, sought political asylum in Australia.

Ah Xian soon began creating sculptural works, initially using plaster and bandages to depict the trauma in China. Gradually, however, his desire to investigate the history and artistic traditions of his heritage grew strong; it gave impetus to what would become an extraordinary body of work in a unique and unbounded sculptural journey. From porcelain, a material celebrated as an important part of Chinese identity for centuries and exhaustively imitated from outside, Ah Xian began looking to other esteemed materials. These include lacquerware, a highly skilled craft that has been traded since the Han dynasty (206BCE – 220CE); green jade, used since Neolithic times; the laborious technique of cloisonné, revered by the court and by scholars after its introduction during the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368); and bronze, the material that helped form civilisation, which defined an age and continues to be heralded as one of the most sophisticated materials, produced in China on an unrivalled scale over history.

In all his experimentation, the human form has remained a central subject in Ah Xian’s work, through which he explores identity, history and human interaction.

Endnotes:

1. Suhanya Raffel and Lynne Seear, ‘Human human’ in Ah Xian [exhibition catalogue], Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 2003, p.9.