We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land on which the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art stands and recognise the creative contribution First Australians make to the art and culture of this country.

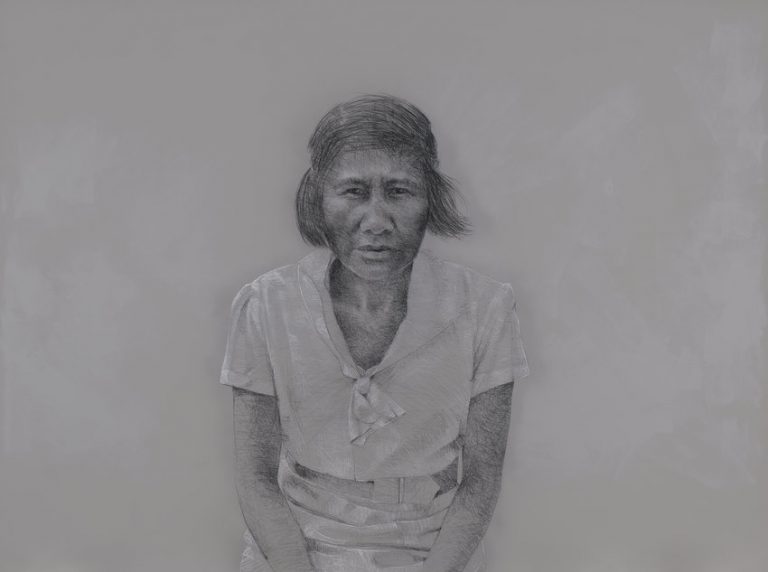

Vernon Ah Kee / Kuku Yalanji/Waanyi/Yidinyji/Guugu Yimithirr people / Australia b.1967 / Annie Ah Sam 2008 / Charcoal, crayon and synthetic polymer paint on canvas / 180 x 240cm / The James C Sourris, AM, Collection. Gift of James C Sourris, AM, through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation 2012. Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Vernon Ah Kee

Vernon Ah KeeAnnie Ah Sam 2008

Not Currently on Display

Annie Ah Sam 2008 is part of a series of large-scale charcoal portraits of Vernon Ah Kee’s family members, both living and deceased.

Many of these portraits are based on photographs taken by Norman B Tindale (1900–93), an anthropologist who documented Aboriginal people between the 1920s and 1960s, in the belief that Indigenous Australians were a ‘dying race’.

Tindale’s images were small and included identification tags, in a similar way to the documentation of a plant or animal species for scientific purposes. Ah Kee re-creates Tindale’s image in large-scale, hand-drawn portraits, from which his relatives gaze directly at the viewer.

Annie Ah Sam depicts the artist’s great-grandmother, who was photographed by Tindale on Palm Island in north Queensland.

Vernon Ah Kee is a Brisbane-based artist at the forefront of conceptual art practice in Australia. He was born in Innisfail and is a descendant of the Kuku Yalanji, Yidinyji and Guugu Yimithirr people of north Queensland. He also has kinship connections to the Waanyi people of north-west Queensland.

Ah Kee developed an interest in art when his family moved to Cairns during his high school years. He studied at the Cairns College of TAFE before moving to Brisbane in 1990. He completed a Bachelor of Visual Arts (with Honours) in 2000 and a Doctorate of Visual Arts in 2007 at Griffith University’s Queensland College of Art. He is a founding member of the Aboriginal Artist collective proppaNOW, and in 2009 he represented Australia at the Venice Biennale.

Vernon Ah Kee is attuned to the politics of representation, and the social and economic implications of unequal cultural exchange in Australia. He often draws on ethnographic archives to challenge colonial legacies and to engage audiences with the strong and continuing presence of Aboriginal Australians, their histories and their cultures.

Many of Ah Kee’s portraits of family members are based on photographs taken by Norman B Tindale (1900–93), an anthropologist who documented Aboriginal people between the 1920s and 1960s, in the belief that Indigenous Australians were a ‘dying race’.

Ah Kee’s portraits are more than a genre-based exploration into the depths of family; they provide a pointed political remark about the past mistreatment of Aboriginal people, whose distrust and frustration can still be felt today. Responding to a history of romanticising Aboriginal people as exotic, or ‘an othered thing’, Ah Kee places Australian history under the microscope to highlight the sense of exclusion that is anchored in museum scientific records. He effectively relocates the Aboriginal in Australia to inhabit real and current space and time; his drawings may be said to not only inhabit, but ‘re-habit’ their space.

Watch

Watch Vernon Ah Kee discuss his portraiture series.

THINK

1. Annie Ah Sam is a portrait of the artist’s great grandmother. What words would you use to describe her? Consider the finer details of the image — her facial expression and body language, for instance.

2. Vernon Ah Kee is interested in the politics of representation. How does the original depiction of this Aboriginal woman as an anthropological or ethnographic study influence our interpretation of the work?

CREATE

1. Create a self-portrait using a digital camera or phone. Construct your photograph as though you were sitting for a licence or passport photo. Using different filters on Instagram or Photoshop, change your portrait to influence the way you want people to view you.

2. Discuss the concept of marginalisation. Identify a group in Australia that you feel is marginalised. Consider the impact of marginalisation on this group and choose a medium that you think best represents it.